In an Assyrian village, a new monument honors life-altering losses

The new monument in Gonda Kosa, situated in northern Iraq, honors Assyrian victims of the Anfal Campaign and other events in Iraq’s history.

The monument for Assyrian Martyrs overlooks the vast green landscape of Gonda Kosa. (Photos/Khlapieel Bnyameen)

Yasmeen Altaji | Apr. 8, 2023

In a rural village in northern Iraq, vast green stretches of tree-lined hills dotted with grazing livestock yield a stark white monument. As of this week, it’s the newest addition to the picturesque landscape of the village to which some Assyrian families in Iraq and in diaspora trace their ancestry.

“I could never live here again,” native Maryam Toma, the sole survivor in her family, whom she last saw as a young girl in 1988, said. “But at least now I have a place to lay flowers and light candles for my family.”

The name of the village is Gonda Kosa, and the unveiling of what is being called the Monument to Assyrian Martyrs this week is the culmination of a months-long project and years-old idea transforming a plot of land on the village’s hillside to a memorialization of what the Assyrian community considers their martyrs of the Anfal Campaign and other events in Iraq’s history.

Memory solidified

On Wednesday, local community members and officials, including members of the Assyrian Democratic Movement (ADM, Zowaa), Assyrian Church of the East (ACOE) Patriarch Mar Awa Royel III and a local troupe of Hammurabi Scouts, gathered at the site for the monument’s unveiling. The ACOE did not respond to The Word’s request for comment.

The monument — a white diamond-shaped structure fitted with the Assyrian flag’s emblematic golden circle, light blue four-pointed star and waved stripes at its center — is flanked on either side by a panel inscribed with Syriac script, one engraved with names of Assyrian victims of the Anfal campaign and the other with names of those killed during other periods, honoring families like Toma’s.

Yacoub Gewargis Yaqo, a native of Gonda Kosa and the Secretary General of the Assyrian Democratic Movement, told The Word the monument was born of an idea he had decades ago, when resources, finances and government initiative were scarce. Yaqo, like some others at the event and watching from the diaspora, is a descendent of one of those killed.

The project was a grassroots effort, a $20,000 USD commitment years in the making, according to Yaqo, who said the idea had been afloat since the 1990s. He said village residents contributed funds themselves and collected donations from the diaspora to build the monument on a communal plot of land “owned by the villagers” once used to collect wheat and barley crops. Locals constructed the monument themselves over the course of five months.

A quaint village with deep history

Situated about 200 km northeast of Erbil, Gonda Kosa — which some say is named for its production of sheep’s wool (kosa meaning hair in Assyrian and gonda a Kurdish word for farmstead) though the name’s origins are debated — is home to fewer than 100 people, according to the Shlama Foundation. In 2021, the nonprofit tallied the village’s population at 72.

But the seemingly small locale is rich with history.

In 1988, several of its residents fell to the Anfal Campaign, a movement of targeted persecution of Iraq’s Kurdish population and other ethnic groups, including Yazidis, Assyrians, Turkmen and Mandeans, by the Ba’athist regime of Iraq. In 1993, Human Rights Watch (HRW) described it as a genocide and estimated between 50,000 and 100,000 Kurds were killed.

The family of Toma, who now lives in Sydney, Australia with her husband and two daughters, are among Assyrian victims. Just about nine years old at the time, Toma is the only member of her family to have survived the campaign.

When word of its onset reached Gonda Kosa, Toma’s father, then the village mukhtar, or chief, found it in the family’s best interest to flee the impending influx of government-led searches and seizures in their village. The family walked for days toward Turkey, where they had hoped to find refuge, according to Toma, during the day hiding in caves to avoid officers’ sight, at night moving in silence.

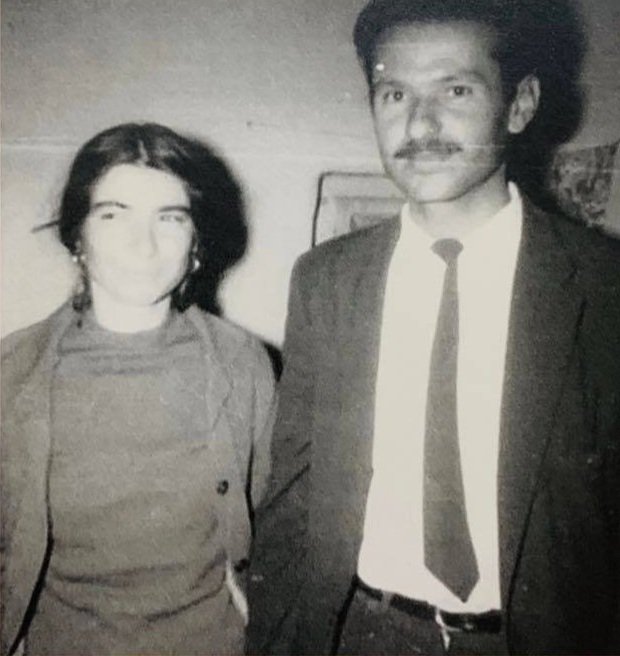

Toma’s father, who her last name honors, was a mukhtar of Gonda Kosa. “This is my favorite picture of him,” she said. (Photo courtesty of Maryam Toma)

They had reached Ankawa, a town in northern Iraq about 190 km away from Gonda Kosa, where they encountered officers who arrested her father and brothers and separated the men and women of the family within what Toma described as a prison holding “thousands of us”.

Alone in a crowded holding facility with her mother Elishwa and sisters Shoshan and Shmoni, Toma came down with an illness. Her aunt smuggled her out of prison and took her to Mosul for treatment. When the pair returned to Ankawa, the rest of the family was gone.

“They said, ‘they have taken them’,” Toma recalled. “Nobody knows what happened. Nobody knows how [my family] were abused or injured.”

According to HRW, several hundred Assyrians, Chaldeans and Yazidis were abducted from camps in the months after the campaigns official end in 1988 and disappeared as “collateral victims of the Kurdish genocide,” the report said. Gonda Kosa alone was home to 34 killed as a result of the campaign.

“We lived there for some time, thinking it was a pure, kind, clean life,” Toma said. “Now, to sleep in the village…I couldn’t. Without my parents, it’s empty.”

For many in the village and in the Assyrian diaspora, the campaign and its martyrs, along with those killed in earlier and later events, are a stark reminder of the village’s history and their own personal ties to it.

“I am a son of this village,” Yaqo, whose grandfather, Yacoub Talia Elia, was an earlier mukhtar in Gonda Kosa, told The Word in a message. “My grandfather, Yacoub, whose name I took, was treacherously killed for defending the land and its inhabitants,” he said.

Nahrain Talia Khoshaba, a Baghdad-born Assyrian raised currently residing in Chicago, is also a grandchild of Elia’s. She told The Word on the phone that family accounts report he was killed by what she described as bandits in the early 1970s along a trip on his mule from Gonda Kosa to the nearby town of Mangesh.

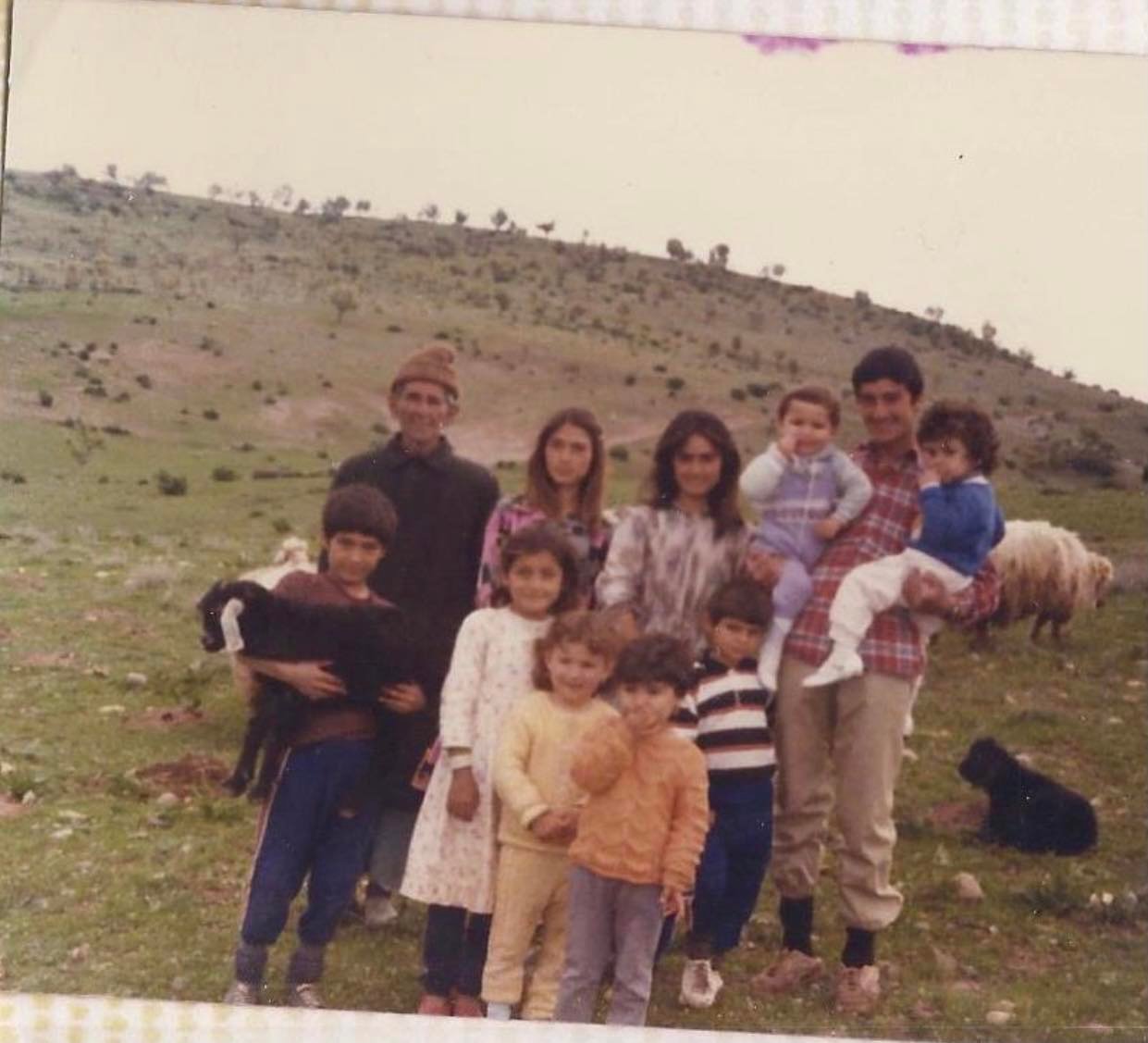

Yacoub Talia Elia (far left), a village chief in Gonda Kosa, poses with his family circa 1958. According to family accounts, Elia was attacked and killed by bandits en route to a nearby village. (Photo courtesy of Ninevehta Khoshaba)

“The reason why myself and my family have been directly affected by our grandfather's death so much is because he didn't die of natural causes, such as old age or illness,” she said.

According to Khoshaba, her grandfather is thought to have been about 82 years old at the time of his death. She said he was known for spearheading initiatives that brought a school, a clinic and a water irrigation system to the village.

Khoshaba thought to search for her grandfather’s name on the monument only when it was unveiled, an event she followed via local posts to social media. She and her daughter, Ninevehta Khoshaba, scanned photos of the monument shared online in search of an inscription of their ancestor’s name. Soon enough, they found it.

“Honestly, it brought tears to my eyes,” Talia Khoshaba said. “I thought of my father. He would have the same reaction…some relief with some tears.”

Robina Lajin stands with her father, Romeo Youela Lajin, in front of the monument at its opening in Gonda Kosa on April 4, 2023. (Photo courtesy of Robina Lajin).

Robina Lajin, who has with paternal ancestry in Gonda Kosa, visited from her home in Germany and attended the inauguration in person. She said the event — and seeing the monument itself — evoked mixed emotions.

“[The martyrs] were killed very brutally. It was very sad, very emotional. I got angry over the things that happened,” she said. “But at the same time, I was very thankful that there's actually a monument.”

Foundations for hope

For Lajin and others, the monument’s inauguration is a reminder of the past and a marker of progress and persistence for their home and community.

“It definitely puts a spotlight on [the community],” she said. “More people will start to think, ‘We need a monument as well in our villages to honor our martyrs.’ I think it's a very good symbol, or maybe, motivation for more villagers to do the same.”

And for Toma, a witness of a hometown now a shadow of the one she knew only to represent joy, childhood and family, finds new purpose in revisiting her village.

“All these years, it was as if there was a heavy rock sitting on my chest,” Toma said. “Coming here, seeing that monument, that weight was lifted. I feel lighter now.”